At least 12 military police involved in deportation violence against Sudanese refugee Ezzedine Mehimmid

On January 5th, Anna was on flight KL0565 from Amsterdam to Nairobi. The Dutch state used the same flight to deport Sudanese refugee Ezzedine Mehimmid. Here’s what Anna reported.

Anger, bewilderment and disappointment among passengers on a deportation flight. On Saturday, January 5, 2019, a KLM flight departed with a young man, mr. Mehimmid, on board. Mr. Mehimmid was forcibly deported to Sudan. It is feared that his life is in danger.

A report on the situation in the plane

Upon boarding, my travel partner and I arrived at our seats in the back of the plane. There was a commotion and we saw several passengers speaking with the military police (Royal Netherlands Marechaussee), who were present on board. I asked a woman traveling with three young children what was going on. She explained to us that a man was being forcibly transported on the flight, in order to bring him via a transfer in Nairobi to Khartoum (Sudan). He was to be handed over there and left to his fate. She asked what we could do to stop this. We knew that the situation in Sudan was extremely unsafe, and couldn’t understand how the man could be forcibly taken there. I’m still thinking about what happened on that flight and it’s important to me to get the story out.

Cries for help were answered with violence from the marechaussee

| In het Nederlands |

Mr. Mehimmid was placed all the way in the back in the last row. The first time we caught sight of him, he was being forced to lie flat on the seats. Three men from the marechaussee were sitting on top of him. A moment later he began to shout, and we saw his face shortly appear above the seats, only to disappear again after a few seconds. The marechaussee were restraining him using sheer force. They covered his mouth to silence him, and his eyes as well. We could only see his feet sticking out and moving.

Passengers don’t think this is “normal”

Meanwhile there was increasing concern and turmoil among the other passengers, who asked questions and exclaimed that they couldn’t believe that this was happening. Multiple passengers came to the conclusion that they were witnessing a violation of human rights and expressed their criticisms and their concerns outright. Both the marechaussee and the KLM staff were proactive in approaching passengers, attempting to justify what was going on and to de-escalate. One of the stewardesses repeatedly said: “It’s normal that they are a bit agitated in the beginning, but then they realize that they really will be deported and they start to calm down later. Don’t worry.” Both she and the Marechaussee emphasized repeatedly that the case had been carefully considered by a judge.

Parliamentary questions and Amnesty International were ignored

Later we learned that the same morning of the deportation parliamentary questions had been submitted by a parliamentarian that critically questions the decision to deport this man. These questions still need to be treated by the secretary of State on this subject, mr. Harbers. Furthermore, Amnesty International Netherlands brought out a report on the Monday after the deportation, that explains that they had urgently requested the secretary of State for Migration and Safety mr. Harbers, months ago, to suspend deportations to Sudan. Research by Amnesty International shows that earlier deportations to Sudan in 2017 and 2018 resulted in detention, abuse, and humiliation.

The Netherlands: intentionally indifferent

The Dutch government does not monitor what happens to a person after deportation. People are handed over at the airport and mr. Harbers’ job is done, despite him being the responsible minister. It is practically impossible for someone who ends up in a dire situation upon deportation to report or seek redress. It is also extremely difficult and often impossible for human rights organizations to acquire information and gather proof upon which to publish and act. These cases are extremely isolated. After seeking more information about this subject with Amnesty International, I learned that in few cases they manage, working behind the scenes, to uncover relevant information about the situation of the deportee. This work requires much patience, willpower, and the use of connections and other means. In most of these cases they can not publicly reveal the information, in order not to jeopardize the security of the people in question. Though in such cases they do inform the Secretary of State. The experience is however that secretary of State responds to these reports with indifference.

The situation in Sudan

It involved a deportation to Sudan, a country which is governed by a military regime which is known for its crimes and the torture of its citizens. It is a known fact that citizens of Sudan who attempt to request asylum in another country are automatically seen as traitors, and that they therefore attract extra attention and face extra danger if they return to Sudan. The International Criminal Court in The Hague has indicted President Omar al-Bashir for genocide in Darfur. Countless reports have been published, including by the Dutch government, on human rights violations in Sudan, ranging from arbitrary arrest to extreme torture and execution by the Sudanese authorities.

KLM and marechaussee are aware of risks associated with this deportation

Once the flight was underway, KLM staff and one policeman of the marechaussee admitted that they understand that the fears over the consequences of this deportation are legit. It is shocking and impossible to comprehend that they nonetheless carry through, even when someone’s life is in danger.

Suppressing criticism

It must have been abundantly clear to all involved parties that with the deportation of mr. Mehimmid, who had come to the Netherlands in order to find refuge, his life would be jeopardized. Nonetheless, no effort was spared to ensure that the deportation would continue as planned. There were many agents of the marechaussee on board, who were there to keep Mr. Mehimmid and other critical passengers under control by all possible means, including violence. At one point we counted 12 policemen in the airplane. Any attempt to film the situation was met with a fierce response from both KLM staff and the marechaussee. Passengers who filmed were forced to erase the footage on pain of being ejected from the flight and arrested. We learned later that the marechaussee had claimed in the media that there had been no threat of coercion to the passengers. This was not how we experienced it, to say the least.

Protest, arrests, and intimidation

Two passengers who continued to protest against the deportation and refused to sit were ordered by the marechaussee to comply. After responding that they wished, before anything else, to speak to the pilot, they were arrested on the spot by at least 4 agents of the marechaussee and roughly forced from the plane via the back door. Having a conversation was impossible. Five minutes later another passenger was also forcefully taken of the plane. One policeman expressed that the situation was getting too crazy. At this point many passengers still refused to sit and there was a strong denunciation of the whole situation: the deportation, the rough behavior of the marechaussee, the ban on filming and the arrests. After about 20 more minutes of intimidation by the marechaussee, and faced with the prospect of violent arrest or missing our flights, passengers complied with the order to sit. One passenger shared with me that she wanted to keep protesting but that she couldn’t afford risking to be kicked off the plane and having to buy new tickets. Another passenger later expressed that he wished he had remained standing. The rest of the flight was rather gloomy, many passengers continued discussing with each other what they had just

witnessed. mr. Mehimmid was guarded for the rest of the flight by 4 members of the marechaussee.

KLM, take responsibility

We call on the staff of KLM to be critical of this sort of situation in the future, to gather information and refuse cooperation. The pilot can intervene. If this had been the case on this flight, it would have earned the respect of us passengers; instead now we are left with bewilderment, anger, and disappointment.

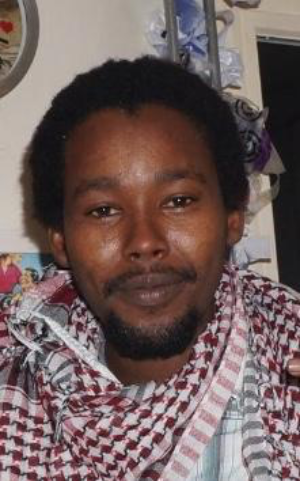

Mr. Mehimmid

In the end the plane departed with mr. Mehimmid on board, against his will and with the outright violation of his most basic human rights. After the flight landed I sought contact with people involved in the case of mr. Mehimmid. I came to understand that sharing information or voicing suspicions about his current situation could place him in more danger. It is deeply unfortunate that the Dutch government has placed him and those close to him in this situation. Our thoughts are with him, and we can only hope, after all the commotion and condemnation this has caused, that the Dutch government will try to save face by making sure he will be brought to safety.

Anna