Film “Do not despair” shows strength and resistance of Indonesian migrants

| Translated by: Jet The original text in Dutch April, 14th 2015 |

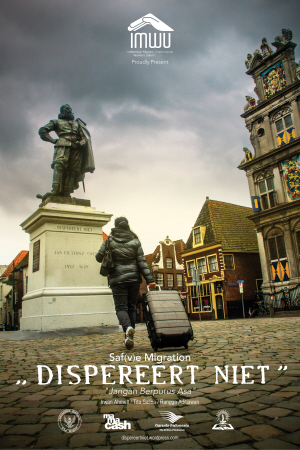

The film is full of beautiful images and symbolism. Ahmett shows to what extent the Dutch city streets still remind us of the colonial past. The film poster shows the statue in Hoorn of the colonial mass murderer Jan Pieterszoon Coen, one of the founders of the Dutch East Indies colony. The film shows a woman with her luggage walking towards the statue: she is a descendent of the former colonised people who migrates to the country of the former colonialist. In an other scene one of the IMWU members walks past a large dilapidated warehouse in Rotterdam that, according to the signs on the walls (“Borneo”, “Java”), in the past was used to store raw materials from the Dutch East Indies, the goods that were obtained through the colonial reign of terror. Further along we see the building formerly belonging to the Holland-America line in Rotterdam to show us that over the years many Dutch people also migrated to various other countries. Simultaneously an Indonesian migrant explains how the Dutch must have experienced this migration in the same way as the Indonesian migrants experience it now. “You leave everything behind and you start with something new”, is the way he puts it, “Because it is a dream, you now, leaving for America.”

Resistance strategies

It is also a dream for many Indonesian migrants. A dream to come to the Netherlands, of course. Criminal organisations are very keen to profit from this. In the documentary a migrant tells about how he met his “travel agent” in a taxi. He was told that he would be able to earn no less than a hundred euros per hour in the Netherlands. He never mentioned the residence permit. “I wanted to go right away”, the migrant explains. But when he arrived in the Netherlands he ended up in a black hole. There was no one waiting for him. He did not have any money and did not speak the language. He asked for food everywhere and sometimes he was given food but more often not. Indonesian migrants pay tens of millions of rupees, amounting to thousands of euros, to go to the Netherlands. Many sell all their possessions to be able to pay the “travel agent”. By migrating they hope to escape poverty and get a better life for themselves and their family members. They need money to be able to send their children to school, to pay for medical treatment for their parents, their partners or others, and to provide for their families. “Who will take care of them if they do not do it themselves?”, says IMWU chair Faisol Iskandar. Some migrate to find the freedom to live their own life, for example transgender Sigita. But also in the Netherlands Sigita is being cold-shouldered, as explained by Yasmine Soraya who is one of the driving forces behind IMWU.

It turns out that the dream of a better life often falls to pieces after arrival in the Netherlands. “It is like a jungle here, you have to fight for your own survival”, according to one Indonesian woman. It is difficult for the migrants to find work without a residence permit. They are badly paid, have problems with their superiors and are afraid that the police will find them. That is why they go into hiding. For months they live in a shed at the place where they work, or hide in the cold storage room for many hours during a police raid. They get caught sometimes, but they provide a lot of support amongst themselves. One scene shows how the migrants talk about the police being on the trail of one of them. During this discussion in the group the roles of support provider and victim merge into one. This is very different from support groups for people without a residence permit: in those cases there is the undocumented person at one end of the table and at the other end there is the (often white) support provider. They live in entirely different and often separated worlds and only meet on this one occasion, and they go their separate ways again afterwards. But the migrants are able to devise resistance strategies because they share their experiences in the struggle for survival. An example is the migrant who says he is not afraid to be picked up because at least he will know how things work in the deportation prison. In the bus to the police station he would be able to advise other undocumented people about what they should say.

Going back

“Each country can belong to everyone and welcome everyone. No one is illegal”, according to Jery, one of the people who are interviewed. “Human beings are people unless you are a cow. How can you forbid a person to get onto a plane and travel to another part of the world?”, he wonders. “Even cows are put on board of planes, even dead bodies. How can they deny us the right to live here, in the Netherlands?” Unfortunately not everyone who is being interviewed in the film has the same assertive attitude. The Indonesian ambassador for example does not speak from the viewpoint of the migrants but looks at things top-down, from the perspective of the state and the capital. His talk makes it clear that such authorities only strive to control migration. He states that migration should be planned and managed from start to finish. In his view, if these things are regulated and happen according to plan and in phases that are controlled by the states, then it will be possible to make a sharper distinction between “desired” migrants who will be admitted and “undesired” migrants who are not welcome and should be deterred. It appears that in the eyes of the authorities such as the Indonesian ambassador the migrants are no more than numbers, units, and abstractions. “We have to contribute to the welfare of the economy”, the ambassador states. And for this it is necessary to use human resources in the most efficient way. The people of flesh and blood seem to disappear in the ambassador’s talk.

Hans van Rhee works for the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and focuses on the migrants themselves. The goal is to have the migrants return to their country of origin: Indonesia. If someone watching the documentary did not know any better they might confuse the IOM with an aid NGO working in the best interest of the migrants. But on closer observation it becomes clear that IOM is only interested in helping migrants return when they are no longer able to cope with the exclusion organised by the state. This is exactly why the IOM was established by the states themselves, as the last cog in the migration control machine. Van Rhee shows himself to be the typical know-it-all white: “It is a different culture, you have changed, you may not feel it right away but it has changed you, believe me.” This is how he talks to an Indonesian woman who probably experienced all of this first-hand already. Almost carelessly the IOM employee tells the story that the migrant probably knows all too well: many do not make it here, they become poor, and lose hope, they give up and return out of sheer necessity. He does not explain that all this misery is caused by his own employer, the Dutch state. He makes it sound as if the migrants are only too happy to return after it becomes clear that they have no future in the Netherlands. But the only thing the migrants might ever be happy about is the one way trip that is paid by the IOM (i.e. a single ticket from the Netherlands to their country of origin) because it means they do not have to pay for the ticket themselves. So on an individual basis the IOM may be of help, but the fact remains that this organisation is and will continue to be a political adversary for everyone who defends the right to free migration. Radna Saptari is a researcher and also advises and supports IMWU, and she looks at the situation from the perspective of the migrants. Legalising means there will be more control, she states in the film. There is indeed an increasing need for protection, against deportation for example.

Big mess

The film is an excellent testimony to the strength and resistance of undocumented migrants in the Netherlands. “You have to be a daredevil, that’s what it means to be illegal.” But in the word of the IMWU chair: “As long as the conditions in Indonesia are such that people do not receive assistance there, they will continue to leave for the Netherlands.” Even if most people in the Netherlands do not welcome them, it is true to say that many Dutch people make use of their services. “The Dutch have houses”, says Jery. “But when both parents have a career to make money for their family, who will clean their house? Who will take care of their children? We do that for them. And when they decide to go to a restaurant for a meal, who prepares the meal? We do that for them. Who does the dishes when they have finished their meal? We do that. If we leave then this country is ruined. If all migrants leave the Dutch will be left in a big mess.”

Mariët van Bommel

Harry Westerink